The Parthenon, Athens, Greece, 447-431 BCE; photo courtesy C. Wayne and Dorothy Miller

Why do we teach a course titled, History of Western Civilization I (and then II)?

Well, the reason for this course goes back to approximately World War I. Before that time, when history was taught in American schools, it was usually ancient history (Greeks and Romans) or American history. With the US involvement in Europe and World War I, there was a movement to more fully explain the origins of the American experiment--connected to the then-current idea of American exceptionalism (see also Wikipedia if that link does not work)--and make the continuous connection from the first democracies of Ancient Greece to the modern United States and thus explaining evolved history of the "western" world. Before long, the history of Western civilization became a standard, required history course taught throughout colleges and universities in the United States.

In the last twenty years or so, there has been a sweeping move, in fits and starts, among historians to replace the western civilization sequence with a world history sequence. Many historians pointed to two key problems associated with the study of "Western Civilization?"

- What do we mean by "civilization?"

- What do we mean by "western?"

The Colosseum, Rome, Italy, 70-80 CE ; photo courtesy Bryan Grasser

So why should you study the History of Western Civilization?

Reason #1. Either of the HIS 101 or 102 courses fills a requirement for a degree or certificate at NVCC (or some other college to which you intend to transfer)--This is actually a bit complicated. 3 credits of any history course are required for the Associate of Science General Studies Degree. For most other degree programs HIS courses fit as a social science elective; but some HIS courses do qualify as HUM electives!

Reason #2. Either course (HIS 101 or HIS 102) fills a convenient open time/date space on your intended semester class schedule.

Reason #3. You have heard that either course (HIS 101 or HIS 102) is an easy class.

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem, 687-691 CE ;

photo courtesy Hoan Soo

Now what about some other reasons?

On the course home page:

HIS 101 reviews the general history of the West from about 3000 BCE to

1600 CE and allows students to reach a basic understanding of the characteristic

features of the West's historical development.

Some of the course objectives:

- Define and describe the importance of key individuals and events in Western history.

- Understand the general chronology and geography of Western history.

- Understand the main forces at work in the historical development of the West.

- Develop an ability to analyze historical sources and reach conclusions based on that analysis.

From Professor DelGallo:

We learn about the origins of our laws and justice system. We see the beginnings of a civilized society. By studying the Roman Empire we see how

a society can rise to greatness and fall because of political and

social issues and outside causes (like many countries and societies

have in the past 200 years).

From Professor Cavey:

G.K. Chesterton once referred to history as "the democracy of the Dead." As an avid fan of history, I had a sense of what he meant. But the more I contemplated it, the more I started to realize a main reason that so many students don't care for history. "This has nothing to do with me because these people are all dead." Some people are racists. Some are sexists. Some are ageist or speciesist. And some have a prejudice against dead people. When we convince students that people in the past got into the same scrapes as they do, argued over the same issues they argue over, and that they make the same mistakes, we see a common vulnerability. As Desmond Tutu once said, "we learn from history that we don't learn from history!" It becomes much easier for a student to empathize with Charlemagne, for example, when the student realizes first, that she or he is possibly descended from him, and second, that there are the proverbial "six degrees of separation" between Charlemagne and the student. Connecting the dots to generations of dead people brings them alive.

From Professor Porter:

The best reason I ever

heard for those who will NEVER take a history class again is:

"After taking His 101

(Western Civ) you will be way more likely to understand some of the

comments people make at parties. It will make you sound much smarter."

Discussions about art, religion, or the ancient Greeks/Romans and how

they are relevant/not for understanding the world today.

From Professor Borgiasz:

Studying His 101 (or His 102) demonstrates to the student that

they are the benefactor of centuries of political, social, and legal

development. Politically, Western Civilization has been the test-bed of

government from aristocracy, oligarchy, to democracy. From the government by

the few over the many, to government by majority. Legally, courts, jury trials,

circuit-riding judges, constitutions all found early starts in Greece and later

Rome. Trial by ordeal, and many of the torturous methods of obtaining the

"truth" so commonly attributed to medieval Europe was ended by the acceptance of

Church canon law. The Renaissance not only contributed architectural wonders

still standing and copied today, but also reinvigorated the study of Greek and

Latin grammar and the classics as models for prose in the 15th century and

beyond. The "subjunctive" sentence structure used by all is derived from the

Latin sentence. Finally, students cannot understand the ideas underlying

their Declaration of Independence or the Constitution without being acquainted

with Greek, Roman, or medieval political thought.

From Professor Blois:

Bertrand Russell once wrote that the essential task of any

education is to overcome "the tyranny of the local." In my humble

view, few things are as effective as a good course in the history of Western Civilization

in cracking this 'tyranny' and letting in some light. Prof. Evans'

links to information about "American exceptionalism" are especially

relevant because, IF the American experience is unique and exceptional, this is

the best reason students in American colleges and universities need a

liberating encounter with people, places, and things from a long time ago in a

galaxy far, far away… ancient and medieval Europe. A famous visual

learner, once sang "Don’t know much about the Middle

Ages; looked at the pictures as I turned the pages." If you want to know

more about the Middle Ages than are revealed in a few photos and maps, you

should take this course. Easy for me to say since I love history…

but after HIS 101, I bet you will too.

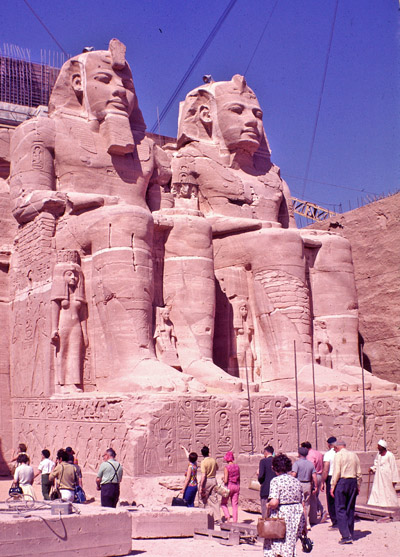

Abu Simbel, Egypt, 1284-1264 BCE; photo courtesy C. Wayne and Dorothy Miller

Some recommended online lectures and websites:

- Penelope J. Corfield, All people are living histories – which is why History matters

- History Relevance

- Peter Stearns, Why Study History?

- For extra credit please suggest to your instructor a

relevant website for this topic. Send the title of the site, the URL and a

brief explanation why you find the information interesting and applicable to

the material being studied in this unit.