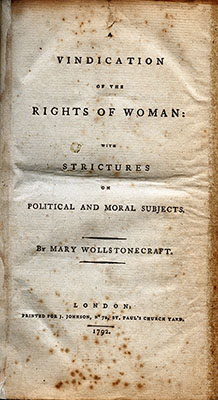

Well, we often study the "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen," produced by the French National Constituent Assembly in 1789, or maybe sometimes the "Bill of Rights" (1791) of the American constitution. But there is another contemporary statement of human rights, and that was A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (1792) by a relatively-then-unknown British woman by the name of Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797). In the famed 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1910-11), she does not even merit an entry, nor does her work. But now she is rather well know as the West's first feminist.

Let's skip her tough upbringing in the household of an abusive father who managed to lose all the family's money, her scandalous love life and affairs (with the American "adventurer" Gilbert Imlay and the British "philosopher" William Godwin), and her suicide attempts (at least twice). That's not why she is important; she is important for her engagement on issues of human rights.

The French Revolution, even more so than the American Revolution (and the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution) provoked a fiery discussion of rights amongst European intellectuals. Edmund Burke's critique of the French Revolution, published as Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), evoked many responses. One of the most important was that of the American political theorist Thomas Paine, who argued in Rights of Man (1791) that revolution was justified when a government infringed the human rights of its citizens. Wollstonecraft also entered the fray with her pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke (1790) in which she attacked the logic of Burke's defense of monarchy and privilege. Her pamphlet brought her a semblance of fame.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is not a short, clear, concise, "catchy" explanation of the human rights of women. In fact, it is a long document, rambling at times, written in a specific, rhetorical, eighteenth-century English. It is difficult to read. I was able to get through most of it, but not all. I'm going to simplify, as I am often prone to do in my notes.

- The most important point made by Wollstonecraft, in my view, is that women should have access to education. The content and scope of that education might be relative to a woman's position in society, but education is important to allow women to contribute to society and to be able to undertake the education of children.

- While she does not explicitly state that men and women are completely the equal of one another, she insists that before God, all are equal. And when it comes to questions of morality, there is equality. It is confusing, but discussions of morality figure prominently throughout the book.

- Women should be seen as "companions" to their husbands, not just "mere wives." Women are not the property or ornaments of men. But Wollstonecraft also criticized women for being focused often on what she called "sensibility." That meant that women could be "flighty," appearance-centered, shallow, focused on the whims of men while women should instead be thinking rationally to improve society.

- In essence, Wollstonecraft asserts, in a round-about way, that women deserve the same fundamental human rights as men.

- On a broader view, she was anti-monarchy and anti-hereditary privileges in favor of a republican form of government in which women could participate.

Wollstonecraft has had increasing influence in the two hundred years after her death. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the women's suffrage movement began to cite her work as important justification for the right to vote. Later, she was seen as important to the birth of a feminist movement in the 1920s and then as the earliest inspiration for second wave of the women's liberation movement. I think that you would also see her work as influential in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

Wollstonecraft was originally buried at Old Saint Pancras Churchyard in London; since 1851 she has been reposing in St Peter Churchyard, Bournemouth. Her tombstone is inscribed: Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: Born 27 April 1759: Died 10 September 1797.

She was the mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley (1797-1851), author of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818).

![]()

Some recommended online resources

- Wikipedia

- Britannica

- Biography.com

- Mary Wollstonecraft at Project Gutenberg

- Mary Wollstonecraft at Internet Archive

- Janet Todd, Mary Wollstonecraft: A 'Speculative and Dissenting Spirit'

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- In our Time (BBC Radio)

- A Vindication of the Rights of Women (Wikipedia); Project Gutenberg copy

- For extra credit please suggest to your instructor a relevant website for this unit of the course. Send the title of the site, the URL and a brief explanation why you find the information interesting and applicable to the material being studied in this unit.