Course

home page

Assignment

Why was

there such a delay in dispersing the National Guard to handle the

angry crowds of the Watts Riots?

Background

1965 was year filled with

both victories and defeats for the Civil Rights Movement.

Although blacks received voting rights with the passing of the

Voting Rights Act, several negative incidents occurred that

affected the black community - Black Nationalist Leader Malcolm X

was killed and the Selma to Montgomery March proved to be full of

violence instead of a peaceful demonstration. The six long days

of a South Central Los Angeles community’s uprising in

August were yet another violent sequence of events that occurred

that year. That uprising would later be known as the Watts

Riots.

For the most part,

the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 greatly improved race

relations in most states, but there were a few exceptions.

California made progress in racial equality by passing the

Rumford Act, which prohibited racial discrimination in the rental

or sale of housing. The Act was a victory for those of poor

black communities, such as those in the South Central Los Angeles

section of Watts, but the California Housing Association did not

share the same positive view. Housing officials did not wish to

enforce the provisions of the Act and therefore proposed

Proposition 14, which repealed the Rumford Act. The citizens of

Watts felt that Proposition 14 would adversely affect them and

that the government betrayed them. They reacted with outrage and

such outrage contributed to the air of violence in the

Riots.

The event

that sparked the Watts Riots began when a 22-year old black

motorist, Marquette Frye, and his 24-year old brother Robert

Frye, were traveling along a Los Angeles street two blocks from

their residence. Suspected of drunk driving, they were stopped

by a white California Highway Motorcycle Patrolman, Lee Minikus.

The younger Frye, who was driving, failed field sobriety tests

and was subsequently placed under arrest. After a squad car was

called to transport Frye and a tow truck called to transport his

vehicle, a crowd began to form. Officer Minikus would not allow

the elder Frye brother to take the car so he walked to his home

to get their mother iso that she could get the car. Upon arriving at

the scene, the Frye’s were not encountered by the small

crowd that they left, but to a crowd of over 250 people. Rena

Frye reprimanded her son and tension grew between the two

of them. The patrolmen noticed such tension and attempted to

subdue Marquette and he began to resist. After this the entire

incident began to spiral downward, with Ms. Frye and her other

son becoming violent with other officers. All three members of

the Frye family were eventually arrested. While the Fryes were

being transported from the scene, an incident occurred in which

someone spit on an officer. The culprit, a woman who was

erroneously reported as being pregnant was also arrested. Rumors

of the Fryes and the woman being treated in an unfair manner

angered the crowd. Although the incident involving the Fryes had

ended, the crowd of more than 1,000 angry people remained on the

scene. The members of the crowd began to vandalize property and

attacking white motorists and police officers until the wee hours

of the morning and subsequently, several were

arrested.

Before the chaotic situation would get

any better, it got much worse over the course of the next few

days. After some of the tension settled the next day, elected

officials, members of the police and sheriff’s departments,

the district attorney’s office and community leaders agreed

to meet to discuss the recent events. Ms. Frye also attended the

meeting. The group attempted to persuade residents to desist the

looting and violence in order that law and order be prevalent,

but to no avail. Instead, groups of blacks met and proposed that

white officers were removed from the Watts area and be replaced

with black officers. White law enforcement officials felt the

proposal would not be advantageous to controlling the situation

and decided to follow procedures already established by the

department. The police chief, William Parker, took matters a step

further; he established a perimeter and made arrangements to

request the National Guard to come to Watts. It was a decision

that needed to be made quickly because it took over 500 law

enforcement officers until 4:00 am the next morning to dissipate

the violent crowds. Before the chaotic situation would get

any better, it got much worse over the course of the next few

days. After some of the tension settled the next day, elected

officials, members of the police and sheriff’s departments,

the district attorney’s office and community leaders agreed

to meet to discuss the recent events. Ms. Frye also attended the

meeting. The group attempted to persuade residents to desist the

looting and violence in order that law and order be prevalent,

but to no avail. Instead, groups of blacks met and proposed that

white officers were removed from the Watts area and be replaced

with black officers. White law enforcement officials felt the

proposal would not be advantageous to controlling the situation

and decided to follow procedures already established by the

department. The police chief, William Parker, took matters a step

further; he established a perimeter and made arrangements to

request the National Guard to come to Watts. It was a decision

that needed to be made quickly because it took over 500 law

enforcement officers until 4:00 am the next morning to dissipate

the violent crowds.

The next

morning crowds began to form again and the National Guard was, in

fact, called to report to the area. But by the time the Guard

arrived, the situation was already out of control. Gang activity

was in progress, snipers were shooting at the police and

buildings were set afire. Rioters yelled, “long live

Malcolm X” and “just like Selma.” After the

Guard arrived the first death occurred when a bystander was

trapped between the violent rioting crowd and the squads of

policemen. As night fell, the rioting crowd began to spread to

surrounding areas, despite having over 1,300 guardsmen in the

area. During this time two more individuals were killed, but

this time they |

were on the 'other’ side;

both a police officer and a firefighter were killed.

After the civil workers were killed, police officers, along with

an additional 1,000 Guard troops, were marching in the streets of

the city anxiously attempting to clear the crowds. This night,

Friday, was said to be the worst night because the rioting never

stopped. Such continued chaos prompted L.A.’s Lieutenant

Governor to impose a curfew that disallowed anyone not pertinent

to controlling the rioting crowds to be on the streets after 8:00

pm. were on the 'other’ side;

both a police officer and a firefighter were killed.

After the civil workers were killed, police officers, along with

an additional 1,000 Guard troops, were marching in the streets of

the city anxiously attempting to clear the crowds. This night,

Friday, was said to be the worst night because the rioting never

stopped. Such continued chaos prompted L.A.’s Lieutenant

Governor to impose a curfew that disallowed anyone not pertinent

to controlling the rioting crowds to be on the streets after 8:00

pm. |

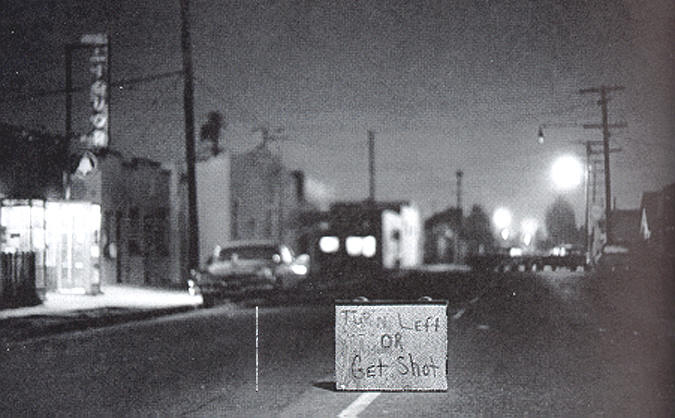

Rioting

continued throughout the next day and the Watts area did not see the least bit of

control until mid-afternoon. When evening came, roadblocks were

set up and the curfew enforced. The Watts area was off limits to

anyone who did not reside there. Although there were a few

instances of fires in stores, there were no major incidents

comparable to those that occurred in the days prior. Rioting

continued throughout the next day and the Watts area did not see the least bit of

control until mid-afternoon. When evening came, roadblocks were

set up and the curfew enforced. The Watts area was off limits to

anyone who did not reside there. Although there were a few

instances of fires in stores, there were no major incidents

comparable to those that occurred in the days prior.

By the next

day, most of the rioting, looting and violent activity had

diminished greatly. California Governor, Pat Brown, visited the

affected areas and even spoke to residents of such areas. Within

three days, all violent activity ceased and the curfew was

lifted.

Although the Watts community, nicknamed

Charcoal Alley, was the center of the rioting activity, the

violence was ‘contagious’ to other areas in

California. Areas as far away as 100 miles were also affected.

San Diego, Pasadena, Pacoima and Long Beach all had incidents of

rioting, fire and other violence. In the end, over 30 people lost

their lives, and over 1,000 people were injured in the riots.

Some estimates of damage to buildings and structures totaled over

$200 million. It may be noted that hardly any of the structures

that were damaged were homes, schools, libraries or churches; the

primary targets were stores and pawnshops. Although the Watts community, nicknamed

Charcoal Alley, was the center of the rioting activity, the

violence was ‘contagious’ to other areas in

California. Areas as far away as 100 miles were also affected.

San Diego, Pasadena, Pacoima and Long Beach all had incidents of

rioting, fire and other violence. In the end, over 30 people lost

their lives, and over 1,000 people were injured in the riots.

Some estimates of damage to buildings and structures totaled over

$200 million. It may be noted that hardly any of the structures

that were damaged were homes, schools, libraries or churches; the

primary targets were stores and pawnshops. |

After the

riots were over, State officials desired to know information

about the details of the incident. Governor Brown initiated a

commission to gather this information and details of such were

reported in Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning?, also known

as the McCone Report. The report indicated that the initial cause

of the riots was far beyond the Frye arrests; it was much

deeper. The violent urban uprising of blacks was due to poor

living conditions, lack of schools and education and the high

unemployment rate. Despite these findings, little or nothing was

ever done to rectify the findings of the report.

The Watts

Riots situation was one of the first incidents in a major city

whose basis was primarily due to housing discrimination. Coupled

with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. other riots for

the same cause occurred in Nebraska, Illinois, Ohio, New Jersey,

and Michigan. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 would contribute

greatly to the enforcement of fair housing as a new federal

agency, Housing and Urban Development (HUD), was created to

perform such duties. HUD not only enforced rules, but provided

funding so that low income families could purchase homes. The

Watts Riots also influenced other minority groups such as Native

Americans, Hispanics and women to seek equal and just

rights.

Timeline

-

1926, a section of south Los Angeles was

named after Pasadena realtor, C. H. Watts

-

2 July 1964, Civil Rights Act signed by

President Lyndon B. Johnson

-

11 August 1965 (Wednesday), 7:00 pm,

Marquette Frye arrested during a routine traffic stop, crowds

formed and looting began

-

11 August 1965, 7:30 pm, Frye at police

substation

-

11 August 1965, between 8:00 pm and

midnight, crowds beat white motorists,

stone cars, etc. Twenty-nine civilians arrested

-

12 August 1965 (Thursday), morning, leaders

of the Watts community met with elected and law enforcement

officials in an attempt to urge people to restore

order

-

12 August 1965, afternoon, Black leader of

the Watts community requested that black officers be used to

enforce law as opposed to white officers. Deputy police chief

rejects the proposal. Soon after the news of such began to

spread to the black community, rioting began

again

- 12 August

1965, early evening, Los Angeles police chief notified the

adjutant general of the National Guard that they may be needed in

the Watts area

- 12 August

1965, later, Emergency Control center at police headquarters

opened

- 12 August

1965, approximately midnight, rioting began and lasted until 4:00

am

- 13 August

1965, approximately 5:00 am, law enforcement withdrawn from the

scene

- 13 August

1965, approximately 8:00 am, crowds began to form again. Calling

the National Guard was anticipated.

- 13 August

1965, afternoon, Governor Pat Brown contemplated initiation of a

curfew due to gang activity and violence in other

cities

- 13 August

1965, approximately 5:00 pm, National Guard officially ordered to

go to Watts. They arrived within an hour and were in staging

areas, ready to go by 7:00 pm. During this time frame, the first

death occurred.

- 13 August

1965, approximately 10:00 pm, Guard troops officially deployed

into Watts.

- 13 August

1965, midnight, an additional 1,000 Guard troops deployed to

Watts. The area was still not under control.

- 14 August

1965 (Saturday) 1:00 am, 100 fire engine companies on site in

Watts. During this time, a firefighter and a deputy sheriff were

killed

- 14 August

1965, approximately 3:00 am, the number of Guard troops grew to

over 3,000

- 14 August

1965, Rioting continues throughout the day, spreading to nearly a

50 square-mile area. This prompted the Governor to officially

impose an 8:00 pm curfew

- 14 August

1965, midnight, Law enforcement officials on site reached massive

numbers - nearly 14,000 Guard troops, over 700 workers from the

Sheriff's Office and over 900 officers from the

LAPD

- 15 August 1965 (Sunday), rioting

was under more control. Governor Brown toured the neighborhoods,

talked to residents.

- 16 August 1965 (Tuesday),

Governor Brown lifted curfew

- 1965,

Governor Brown initiated a committee, The Governor's Commission

on the Los Angeles Riots, to study the chronology, events and

alleged causes of the riots. The results were reported

in Violence in the

City: An End or a Beginning?

WWW

sites

Video

clips of footage taken during the Riots, as well as, Huey

P. Newton's story of the event may be viewed at

PBS.com.

The entire McCone Report and additional information may be reviewed at

the University of Southern California's website.

Several government agencies

have collectively sponsored a site that details historic

places during the Civil Rights Movement. Links to other

pertinent sites may also be found.

Details of Civil Rights

Movement exhibits and information may be found at the National Civil

Rights Museum website.

Also

Recommended Books

- Books accounting the events of the Riots:

Bullock, Paul. Watts: The Aftermath; An Inside View of the

Ghetto. New York: Grove, 1969. ; Cohen, Jerry and William

S. Murphy, Burn, Baby, Burn! The Los Angeles Race Riot,

August 1965. New York: Dutton, 1966; Conot, Robert. Rivers of Blood,

Years of Darkness: The Unforgettable Classic Account of the Watts

Riot. New York: Morrow, 1968; Crump, Spencer. Black Riot in Los Angeles:

The Story of the Watts Tragedy. Los Angeles: Trans-Anglo,

1966; Fogelson, Robert. The Los Angeles

Riots. New York: Arno, 1969; Sears, David. The Politics of Violence:

The New Urban Blacks and the Watts Riot. Boston:

Houghton, Mifflin, 1973.

Related Events |

Before the chaotic situation would get

any better, it got much worse over the course of the next few

days. After some of the tension settled the next day, elected

officials, members of the police and sheriff’s departments,

the district attorney’s office and community leaders agreed

to meet to discuss the recent events. Ms. Frye also attended the

meeting. The group attempted to persuade residents to desist the

looting and violence in order that law and order be prevalent,

but to no avail. Instead, groups of blacks met and proposed that

white officers were removed from the Watts area and be replaced

with black officers. White law enforcement officials felt the

proposal would not be advantageous to controlling the situation

and decided to follow procedures already established by the

department. The police chief, William Parker, took matters a step

further; he established a perimeter and made arrangements to

request the National Guard to come to Watts. It was a decision

that needed to be made quickly because it took over 500 law

enforcement officers until 4:00 am the next morning to dissipate

the violent crowds.

Before the chaotic situation would get

any better, it got much worse over the course of the next few

days. After some of the tension settled the next day, elected

officials, members of the police and sheriff’s departments,

the district attorney’s office and community leaders agreed

to meet to discuss the recent events. Ms. Frye also attended the

meeting. The group attempted to persuade residents to desist the

looting and violence in order that law and order be prevalent,

but to no avail. Instead, groups of blacks met and proposed that

white officers were removed from the Watts area and be replaced

with black officers. White law enforcement officials felt the

proposal would not be advantageous to controlling the situation

and decided to follow procedures already established by the

department. The police chief, William Parker, took matters a step

further; he established a perimeter and made arrangements to

request the National Guard to come to Watts. It was a decision

that needed to be made quickly because it took over 500 law

enforcement officers until 4:00 am the next morning to dissipate

the violent crowds.

were on the 'other’ side;

both a police officer and a firefighter were killed.

After the civil workers were killed, police officers, along with

an additional 1,000 Guard troops, were marching in the streets of

the city anxiously attempting to clear the crowds. This night,

Friday, was said to be the worst night because the rioting never

stopped. Such continued chaos prompted L.A.’s Lieutenant

Governor to impose a curfew that disallowed anyone not pertinent

to controlling the rioting crowds to be on the streets after 8:00

pm.

were on the 'other’ side;

both a police officer and a firefighter were killed.

After the civil workers were killed, police officers, along with

an additional 1,000 Guard troops, were marching in the streets of

the city anxiously attempting to clear the crowds. This night,

Friday, was said to be the worst night because the rioting never

stopped. Such continued chaos prompted L.A.’s Lieutenant

Governor to impose a curfew that disallowed anyone not pertinent

to controlling the rioting crowds to be on the streets after 8:00

pm. Rioting

continued throughout the next day and the Watts

Rioting

continued throughout the next day and the Watts Although the Watts community, nicknamed

Charcoal Alley, was the center of the rioting activity, the

violence was ‘contagious’ to other areas in

California. Areas as far away as 100 miles were also affected.

San Diego, Pasadena, Pacoima and Long Beach all had incidents of

rioting, fire and other violence. In the end, over 30 people lost

their lives, and over 1,000 people were injured in the riots.

Some estimates of damage to buildings and structures totaled over

$200 million. It may be noted that hardly any of the structures

that were damaged were homes, schools, libraries or churches; the

primary targets were stores and pawnshops.

Although the Watts community, nicknamed

Charcoal Alley, was the center of the rioting activity, the

violence was ‘contagious’ to other areas in

California. Areas as far away as 100 miles were also affected.

San Diego, Pasadena, Pacoima and Long Beach all had incidents of

rioting, fire and other violence. In the end, over 30 people lost

their lives, and over 1,000 people were injured in the riots.

Some estimates of damage to buildings and structures totaled over

$200 million. It may be noted that hardly any of the structures

that were damaged were homes, schools, libraries or churches; the

primary targets were stores and pawnshops.