The Alliance was the tsar's idea. Historians disagree about the real roots of the idea, but most tend to attribute some influence to the mystic Barbara Juliane von Krüdener. During the late campaigns against Napoleon, the tsar had become increasingly preoccupied with mystical and spiritual matters. He proposed the Holy Alliance, allegedly to promote Christianity in European political affairs, but in reality the Alliance became a mechanism to keep the existing European order. In time, the other rulers in Europe signed the alliance except for King George IV of England, the pope and the sultan, who was not a Christian.

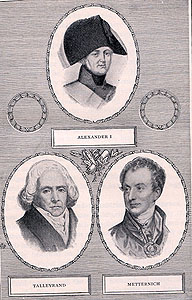

In some respects, the Holy Alliance served as propagandistic camouflage for one of the Western world's first international peacekeeping organizations--the combination of Prince Metternich (actually, Prince Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneberg-Beilstein), who was Austria's Foreign Minister, and Viscount Castlereagh (actually The Most Honourable Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry), who was England's Foreign Secretary--that attempted to repress any outbreaks of revolutionary sentiment in Europe.

Interestingly, the Monroe Doctrine in the United States was, in part, somewhat connected to the Holy Alliance in that in both cases the fear of revolutionary unrest served as the pretext for the right of other powers to intervene to maintain the existing order.