Roscoe Berlin (1889-1933) was the fourth of nine children of A. P. Berlin and Abbie Gardiner.

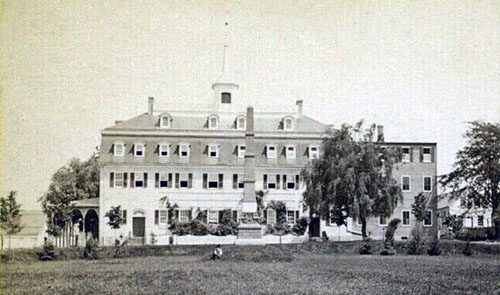

As a boy he attended the Nazareth Hall Military Academy, a boys boarding school located in Nazareth, PA about ten miles east of Slatington. That was an interesting school that went by a few different names (Nazareth Hall, Nazareth Hall School for Boys, Nazareth Military Academy), but, in reality, it was never a military academy.

The school, which existed from 1752 to 1929, was founded by the local Moravian church community as a central boarding school. At first, the school only accepted boys aged seven to twelve who were sons of Moravian clergy. Later, the school was opened to other boys in the community. In 1785, it became a general boarding school that emphasized a classical education as well as vocational training and religious instruction. In 1862, the school principal organized the boys into a uniformed cadet company, and he introduced military drill as part of a routine of physical education. It was at this point in time that Nazareth Hall gained its reputation as a military academy. Currently, the building is still standing and is in use as an apartment building.

Photo credit Lehigh Valley History on Facebook

Roscoe graduated from Lafayette College in June 1911. While there we have some idea that he worked as a core driller, most likely with his father’s company, the Prospect Drilling and Developmental Company. He also seems to have spent some time (1910-1911) at a mining engineer school, the Michigan Mining School (now called Michigan Technological University aka Michigan Tech), in Haughton, Michigan.

After graduating from Lafayette, Roscoe remained in Slatington. In February 1912 he was appointed borough engineer, a position he held until April 1915. While in town he was also active organizing the first Boy Scout troop. In October 1913 he left for Murray, Idaho to take up a job as a mining engineer. This was a thriving gold rush town with mining active there between the 1880s until it died out by 1950. For three years he would be back and forth between Murray and Slatington. On 26 January 1916, he was back in town where he married Sarah Main Bowers (1890-1964), daughter of Charles Bowers and Mary Bowers nee McLaughlin. Sarah was a local telephone operator. After the marriage, they headed back to Murray, Idaho.

Eventually, the war caught up with the Berlin family. Roscoe was required to register per the 5 June 1917 registration date, which he did. On his registration form, he listed his occupation as mining engineer, employed by Taylor Wharton Iron & Steel of High Bridge, NJ and eastern PA. (The firm is still in existence.) In the summer of 1917, he enlisted and was commissioned a first lieutenant in the engineers. At the end of August, he proceeded to the Engineering Officers’ Reserve Corps at American University in Washington, DC where the newly-organized 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame aka “Hell Fire Boys”) was setting up its training headquarters. A year later, 13 July 1918, the regiment was re-designated as the 1st Gas Regiment.

As a side note, Roscoe’s brother, Harold, also served in the army during the war as did two of his brothers-in-law (Carleton Kidney and Douglas Reed).

With his activation as an officer in the engineer regiment, Roscoe’s war service generally aligned with the activities of the gas regiment except for a few days in early December 1917 when he returned to Slatington on a short furlough. Eventually, he was promoted to captain (24 December 1917) and then major (15 October 1918).

World War One saw the first large-scale use of chemical weapons in a war, and that necessitated the creation of specialized army units trained to employ gases such as chlorine, phosgene, and mustard. The Germans first used chlorine gas on 2 April 1915 at Ypres, Belgium, and soon thereafter the French and British also began using the gas. By the time the United States entered the war in April 1917, gas was a prominent part of every battlefield. Yet, at that time the US entered the war, the army had made no real preparations for dealing with reality of gas warfare. When war was declared, the army had no gas masks, gas weaponry or gas expertise.

On 30 August 1917, Major (later colonel) Earl J. Atkisson (1886-1941) was assigned the task of raising and training a new gas regiment at American University in Washington, DC. That was a weird choice given the site’s proximity to the White House (only about four miles to the northwest). Roscoe Berlin was part of the earliest cohort of officers in the new regiment. Eventually, training was also carried out at Fort Myer Army Base, across the Potomac River in Virginia.

Camp American University, Washington, DC

Camp American University also functioned as a chemical warfare research lab and testing site. The service manufactured smoke screens, gas bombs, “flaming guns,” projectiles filled with explosive and incendiary material and many more types of weapons. Cleanup and disposal at the American University site was still going on as late as 2002. See, for example, Jacob Fenston, “Cleanup Complete at WWI Chemical Weapons Dump in DC’s Spring Valley.” (Accessed at www.npr.org)

Captain Atkisson set out gathering officers, enlisted men, equipment and information. Beginning in October 1917, the influx of enlisted personnel into the regiment was "near continuous". Since initially the army had no chemical warfare experience, weapons or equipment, training consisted mostly of close order drill, marching, inspections and guard duty.

The first men (companies A and B) from the gas regiment reached France in mid-January 1918 with companies C and D following in March. Only after these companies arrived in France, without any gas masks or gas weaponry, did they begin to receive training from the British Special (Chemical) Brigade at Helfaut, France. There the Americans learned the use of Livens projectors and Stokes mortars. After training was completed, American platoons were attached to British special engineer companies.

The Livens projector and the Stokes mortar were the primary gas weapons used by the Americans. On a stationary front, the Livens projectors were deployed in a battery of twenty. Each projector was basically a steel drum or large pipe weighing about 140 lbs. that was half-buried in the ground. When triggered, each drum fired a large canister of gas up to a distance of as much as 1700 meters. The projectors were wired to fire electronically in a large salvo. On a more active front, men fired the Stokes mortar which was basically a simple steel tube (a bore of either 3” or 4,” weighing 96 lbs.) A five-man team could fire over twenty rounds per minute with a maximum range of about 800 meters. The Stokes mortar could be used to fire ammunition that included smoke, gas and thermite.

Through the summer of 1918, while some American gas units saw action at Chateau-Thierry or when assigned to British units, most men spent their time repairing roads and burying the dead. Originally, Berlin was in charge of training new soldiers as they arrived in France, but later he took command of Company D and was under fire in several actions.

With the formation of the American First Army in August 1918, the gas regiment ceased to operate with independent French and British units and became part of the American army. The battalions (two companies each) were assigned to corps and the companies to divisions throughout the St. Mihiel (12-15 September) and Meuse-Argonne (26 September – 11 November) operations.

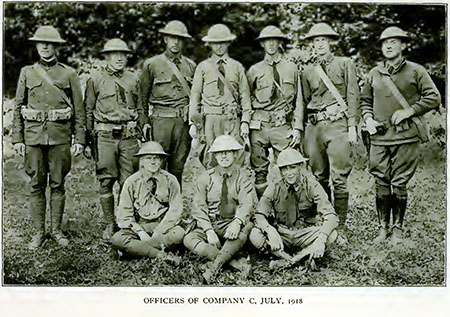

Photo of some 1st Gas Regiment officers

In these two battles, the units of the 1st gas regiment were assigned all along the American front, supporting the individual infantry divisions. Men in the regiment used their Stokes mortars to support advancing infantry by taking out enemy machine gun positions and strong points by firing combinations of gas, smoke, and thermite. During these operations, Captain Roscoe Berlin commanded the provisional battalion (companies A and F) before being dispatched back to the US to begin training additional battalions.

The war ended while Roscoe Berlin was in the U.S. On 10 October 1918, he had reached Hoboken, New Jersey aboard the USS Agamemnon. In two days, he was back in Slatington on a short furlough, and the war ended before his return to France. He was discharged by the end of the year.

For his service with the 1st gas regiment, Roscoe Berlin was awarded the distinguished service medal. He had been in the front lines several times and participated in the Somme defensive, Champagne-Marne, Aisne-Marne, Oise-Aisne, St. Mihiel, and Meuse Argonne battles.

After the war, Roscoe Berlin returned to Slatington and re-involved himself with the slate business. In February 1919, he left on a business tour of England, Belgium, France and Germany, and that summer he was part of the founding meeting of the Allen O. Delke American Legion Post 16, Lehigh County’s oldest post.

In those years, Berlin was also involved with efforts to better organize the slate trade on a regional and a national level. He was a director of the Structural Slate Company, a consulting company that coordinated the slate output of some 25 quarries in Lehigh and Northampton counties. In April 1922 he became a member of the executive committee of the National Slate Association which was organized in New York. (The association met in Slatington in August 1923.) He also wrote an extensive article for The Morning Call on the local history of the slate trade, “Slatington, The Center of Natural Resources.” (The Morning Call, 18 June 1922)

In March 1924, Roscoe resigned as superintendent of his father's Genuine Washington Slate quarries, a position that he held for several years. That was about a month before his father died. In the ensuing years, Berlin and his family migrated back and forth between California and Slatington. In California, Berlin operated an orange grove and was involved with the manufacture and marketing of fruit juices. By early 1933, Roscoe and his family were back in town, living in the Berlin house on First Street. He was especially actively involved with the welfare association committee work in town and overseeing work on the community wood pile, cutting wood and distributing it to needy families in the midst of the Great Depression.

Then, the headline of The Slatington News on Thursday, 11 May 1933 read: “Death Claims Major Berlin.” His car had plunged into the abandoned Penn Lynn quarry at about 10 pm on Friday, May 5th.

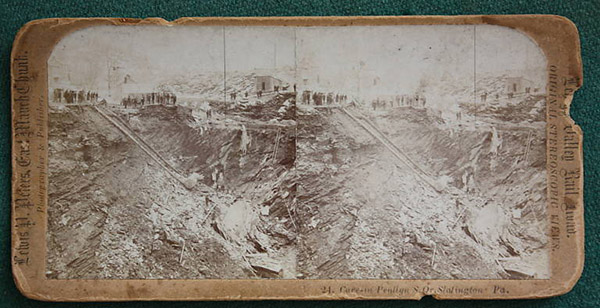

The quarry (aka Pen llyn or Pennllyn or Pen Lynn or Pennryn) quarry was an old quarry on West Church Street, roughly just northeast of the intersection of Fifth and Church Streets in Slatington. According to the 1927 survey of slate quarries in Pennsylvania (Slate in Pennsylvania, 1933), the size of the quarry was estimated at about 190 x 275 feet and said to be at least 150 feet deep and filled with water.

Early stereoscope photo of the quarry

The quarry was opened by D. D. Jones and Hugh Hughes in 1864. Ownership of the quarry changed hands several times in the succeeding decades. At one time it was leased and operated by the Old Lehigh Slate Company which produced school blackboards.

Over the years of operation there were numerous accidents at the quarry. Several times there were cave ins, and in 1898 one man was killed and others injured in one of those cave ins.

1938 Aerial view of the Penn Lynn quarry location

By the early 1900s the quarry appears to have been flooded, although there were still occasionally efforts to re-open the quarry.

By 1930, a fence had been erected around the abandoned quarry. And in 1932, I found a note in the newspapers that the borough, which had acquired the quarry, had prohibited dumping. (It was a rather common practice to use an abandoned slate quarry as a dumping spot. I remember this still going on at abandoned quarries in the Slatington area as late as the 1970s.)

According to accounts of Major Roscoe Berlin’s death, he had headed out to Slatedale on Friday evening, May 5th, to secure a truck for the delivery of lumber and flour by the charitable relief cooperative that he had organized. He headed west on Church Street in his black sedan. A witness, David “Mulgie” Jones, was standing in the vicinity. Jones stated that he saw a big black sedan pass by, and then he heard a crash as the car went through the wooden fence and into the quarry at about ten o’clock. Jones spread the alarm, and soon the chief of police, Ralph Griffith, and burgess, P. N. Snyder, were on the scene. Quickly a large crowd gathered. Oscar Scheetz brought a small skiff to the scene. Five men rowed out into the quarry and found gasoline floating on the water and also a hat, tire, book, and car seat. On Saturday some men working with ropes and grappling hooks located the position of car about 50 feet down in the quarry.

Burgess Snyder contacted the Life Saving Corps of the Allentown Chapter, American Red Cross who, in turn, contacted Charles Scully of the Life Saving Division of the American Red Cross in New York. Scully contacted John Ingram, a diver for the Chapman and Scott Marine Salvage Corp. Ingram and his assistant, J. C. Trahan, arrived in Slatington at about 5:30 PM on Saturday. On a 14’ x 14’ raft, Ingram entered the water at about 7:15 and found the badly damaged car on a ledge about 60 ft. down, but he could not find the body. A Pennsylvania Power and Light truck was able to hoist the car briefly around 7:45, and it was identified as Roscoe Berlin’s car. But then the line snapped, and the car went back into the quarry about 25 ft. down.

On Sunday morning, the search resumed, and a little before nine o-clock Ingram was able to quickly locate and retrieve Berlin’s body. By that time, hundreds of people had gathered to witness the activity. All day long curious people visited the site. “Members of the State Highway Patrol were on duty in the vicinity, just as they had been all day Saturday, assisting the police of the borough in directing traffic, the parking of hundreds of automobiles and looking to the safety of the onlookers in the vicinity of the quarry.” (7 May 1933, The Morning Call)

The body was removed to undertaker Berkemeyer, and coroner A. M. Peters of Allentown was called. An autopsy performed by Dr. Jon Wenner of Allentown Hospital resulted in a conclusion, "death due to drowning." The coroner’s inquest on Monday evening agreed, “accidental death by drowning.”

A viewing was held that Monday evening at the home of Berlin’s mother on First Street, and the funeral took place at 2 o’clock the following afternoon.

After Roscoe Berlin’s death, later that year some men were put to work filling in the quarry as a Civil Works Administration (CWA) project, but that effort did not get very far. In the decades that followed, people continued to dump stuff into the quarry, and the borough continued to debate what to do with the site to eliminate any hazard.

Then, in 1963 there was some movement. That year the borough sought bids to fill in the quarry so that the site could be sold, and in September, Acme markets (American Stores), which already had a store at 661 Main Street (first opened in 1914) in Slatington, bid $500 for the site. A contractor was charged with pushing the slate refuse into the quarry. On the site of the former slate refuse bank, a new Acme market was built. The store opened in October 1964. (In the late 1960s and the 1970s, I shopped there often with my grandmother.)

Photo of the early Acme store

When the Acme market ceased operations decades later, the store stood idle for years. The Acme site today is now Dorward Electric Co. The company was started in 1978 by Jeff Dorward and is now owned and operated by Kevin Geist.

Dorward Electric

While the Acme store opened, some of the quarry immediately to the west of the store still remained, just partially filled in. Occasionally, the borough considered creating a Penn Lynn Park, but that never happened.

When I was growing up in the 1960s and early 1970s, the quarry was just a pond of sick-looking water, maybe a few feet deep in places. Occasionally, when it was cold in winter, the ice was thick enough to be used for ice skating. It was pretty evident at the time that a lot of junk had been dumped into the quarry over the years.

Eventually, the site was completely filled in, graded and used as the site for the borough maintenance buildings and the Slatington fire department. Below is what the site of the quarry looks like today.

Current photo (2023) of the Penn Lynn quarry site

Roscoe was buried in Fairview Cemetery. His wife, Sarah, died in 1964 in Drexel Hill, PA where she had been living since about 1934. She was also buried in Fairview cemetery. There were two children in the family: Bruce Berlin (1920-2017) and Mary Berlin (1922-2022). The son, Bruce, was also buried in Fairview cemetery. According to his obituary, he was an army and air force veteran who served as a first lieutenant in both World War II and the Korean Conflict. During his service, he was awarded two bronze stars and a purple heart medal. He was predeceased by his wife Olga A. (Flaga) Berlin (1923-2013). Mary Berlin married Doctor Kenneth W. Benjamin (1915-2004) in 1946, and they lived in the greater Philadelphia area. They raised three children.