![]()

Ideas

World War I was the most devastating the world had ever known to that time. (6) By the end of the war, the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish-Ottoman Empires no longer existed, and there was a political vacuum that spanned Central and Eastern Europe and the Near East. The world expected a peace settlement to restore hope, feed the hungry, restore democratic institutions and draw new borders.

Woodrow Wilson, led the way in trying to fulfill those expectations. As early as 8 January 1918 in a speech to a joint session of Congress, he had outlined the guiding principles that should make up a postwar settlement, the Fourteen Points. His opening paragraph left no doubt as to his intent:

It will be our wish and purpose that the processes of peace, when they are begun, shall be absolutely open and that they shall involve and permit henceforth no secret understanding of any kind. The day of conquest and aggrandizement is gone by; so is also the day of secret covenants entered into in the interest of particular governments and likely at some unlooked-for-moment to upset the peace of the world. It is happy fact, now clear to the view of every public man whose thoughts do not still linger in an age that is dead and gone, which makes it possible for every nation whose purposes are consistent with justice and the peace of the world to avow nor at any other time the objects it has in view. (7)

The Twelfth Point made specific reference to the peoples that were at that time still under Ottoman rule: "The other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development". (8)

Wilson took seriously the idea of self-determination. In a second speech to congress on 11th February 1918, he said, "Every territorial settlement involved in this war must be made in the interest and for the benefit of the populations concerned." (9) The British and the French publicly issued a joint communique describing the war against the Ottoman Turks as being fought for the emancipation of the oppressed peoples of the region and that the people of the region would be allowed to form governments that derived their respective authorities, not from an occupying power, but from the indigenous people. The British and the French however, still had their own secret designs on the Middle East. (10)

When the time arrived for politicians to arrive in Paris, not everyone gathered there shared the views espoused by President Wilson. The French concentrated on protecting their border with Germany. The British were bent on protecting their Empire, in particular, the routes needed to ensure safe passage for those traveling on Empire business. The Italians were interested in creating a new Roman Empire.

The situation in the Middle East definitely was not one where all parties subscribed to Wilson's notion of self-determination. As early as 1916 Britain and France had secretly agreed to divide the Middle East between themselves in anticipation of victory in the war.

Sykes Picot Agreement of 1916

In November 1915, the British entered into secret negotiations in London with the French over the rights and claims of both powers in the Middle East. (11) Sir Mark Sykes, a member of the British War Cabinet, (12) had responsibility for negotiating with France. He was pro-French, a Catholic who sympathized with the French position of promoting Catholic interests in Lebanon and a man who had lived and traveled in the Middle East.

François Georges Picot, (13) a career French diplomat, was dedicated to the idea of a French controlled Syria. Earlier in 1915, Picot had launched a successful campaign in the French Parliament against members who were inclined to give way to the British over the Middle East. Picot and the French leadership desired control over Syria and Lebanon. The latter was perceived as necessary to the French so as to give Syria access to the Mediterranean Sea. The French also wanted to extend their Syrian influence eastward to include the town of Mosul in what today is Northern Iraq.

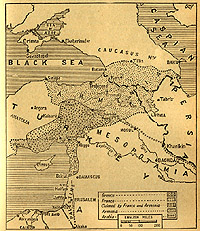

The French intentions suited the British position very well. Hubert Horatio Kitchener, Secretary of War, (14) who was directing the negotiations from behind the scenes on behalf of the British Government, saw great advantage to having the French placed between the British in Mesopotamia and the Russians in the Caucasus. In the end, the French and the British reached what was for them the perfect compromise; France was to have control over Lebanon and influence over Syria as far east as Mosul. Britain was to have control over Palestine, Trans-Jordan and Mesopotamia. (See Appendix E.)

The Balfour Declaration

A complication to Anglo-French intentions towards the Near East occurred on 2 November 1917, when Britain published the Balfour Declaration. (15) The declaration read,

His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. (16)

As early as 1906, Lord Arthur Balfour (17) had met Chaim Weizmann, (18) a naturalized British Jew who eventually became the leader of the World Zionist Movement. At that time, Weizmann presented to Balfour his case for a Jewish homeland. Weismann met Balfour again in 1914. According to Weismann, at that time, Balfour was convinced by the arguments for a Jewish homeland in the Middle East. (19)

Both the French and the Arabs opposed the notion of a Jewish national home. In 1916, the French government had objected to a suggestion by Britain that the allies issue a public, pro-Zionist statement. (20) For their part, the Arabs saw Palestine as an integral part of an autonomous, independent Arab state. They were not fighting for their independence just to give a portion of the land away; especially a portion that contained the third most Holy site in Islam. In the end, these territorial and other issues were supposed to be resolved in Paris. It was precisely to address the issues of the Middle East that Lawrence found himself in Paris as an aide to Prince Feisal.

Background of T. E. Lawrence

Lawrence came to Paris with the sole aim of persuading the Great Powers of the legitimacy of the Arab claim to an independent state. Born on 16 August 1888 in Tremadoc, Caernarvonshire, North Wales, he was the second son of Sir Thomas Chapman and Sara Maden. Sir Thomas had left his home, wife and five daughters in Ireland, to live with Sara, who had previously been governess to Sir Thomas' daughters. After a somewhat nomadic life the family settled in Oxford under the assumed name of Lawrence. T. E. Lawrence attended the City of Oxford High School for boys and went on to Jesus College, Oxford, where he gained a first class honors degree in history for his thesis on Medieval military history. While researching his thesis, Lawrence visited historical settings, including, in 1909, sites in Syria and Palestine. (21)

A protégé of the Oxford archaeologist, David George Hogarth, (22) Lawrence was awarded a travel fellowship from Magdalen College, Oxford from 1911 until 1914. He joined an expedition excavating the Hittite settlement of Carchemish on the Euphrates River as an archaeologist, first under the tutelage of Hogarth and then later Sir Leonard Woolley, at the time an assistant director at the Ashmoleum Museum in Oxford. In his free time, Lawrence explored the local countryside, learned the language and observed the traditions and customs of the indigenous people. He became enamored of his surroundings and immersed himself in the local Arab culture.

It was during his time in Carcemish that Lawrence met and befriended an Arab boy named Ahmed Dahoum. When Lawrence fell ill it was Dahoum who nursed him back to health. (23) His time at Carchemish caused Lawrence to develop an affinity for the Arabs. Lawrence summed up his feelings for Carchemish, after a brief time away, when he wrote, "I seem to have been months away….and am longing for its peace. You know there, one says, 'I don't want to talk' and there is silence until you break it…..Really, this country, for the foreigner, is too glorious for words." (24)

Early in 1914, together with Woolley, Lawrence joined with Captain Stewart F. Newcombe of the Royal Engineers. Permission had been obtained from the Turks for a British survey of the northern Sinai on the Turkish frontier east of Suez. (25) It was supposedly an archaeological expedition, but in reality it was a map-making reconnaissance of the region spanning Gaza to Aqaba. The reason for the survey was to map the land that was in close proximity to Egypt and Palestine but had not yet been explored by the British. It was here that Lawrence added the skill of cartographer to his resume.

Early Years of the War

Although war broke out in Europe in August 1914, it did not immediately reach the Middle East. Only in November 1914, did Sultan Mehmed V of the Ottoman Empire call for a jihad (Holy War) against the allies, and he brought the Ottoman Turks into the war on the side of the Central Powers of Germany and Austria. (26) Even though the call for a jihad went largely unanswered in the Muslim world (the idea of allying a Muslim Holy War to the aims of a Christian belligerent was to many, absurd) Britain decided to launch a preemptive strike against Turkish positions. An Anglo-Indian force was dispatched to Basra, a town near to the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in Southern Mesopotamia, (27) to protect the Anglo-Persian oil pipeline. (28)

The Central Powers responded to the arrival of the British on the Euphrates by launching an attack against the British at Suez. (29) This attack failed but encouraged the British to turn some attention from the Western Front in an effort to force the Turks out of the war. The strategy included an Egyptian Expeditionary Force, the mission of which evolved from a defense of Egypt to an invasion of Palestine. (30)

By December 1914 Lawrence was a lieutenant in military intelligence based in Cairo with the Cairo GHQ. (31) The expertise he offered was a rarity in the British military machine. Not many people could offer knowledge in the way of the Arabs, and he had also traveled in Turkish held Arab lands. He spent about a year in military intelligence interviewing prisoners, drawing maps and receiving and interpreting intelligence information from agents operating behind the enemy lines.

The Arab Revolt

In December 1915, Sir Mark Sykes reported to his government that should Britain launch an invasion of Palestine and Syria, it would trigger a revolt against the Turks by the Arabic-speaking peoples of the region. Such a revolt had been declared the previous June by Hussein ibn Ali, Sherif and Emir of Mecca, but it had failed to materialize. Events leading to Sykes' claim included an "elaborate interchange of letters" (32) between Sir Henry McMahon, His Majesty's High Commissioner in Cairo, and Hussein in which "Hussein made quite clear what were his aims and those of his friends. They were seeking to achieve Arab independence." (33)

In October 1916, Lawrence accompanied the diplomat Sir Robert Storrs on a trip to Jeddah, a Red Sea port in Arabia. Storrs had to report to one of Hussein's sons, Abdullah ibn Hussein that, despite assurances to the contrary, His Majesty's Government would not be sending troops and aeroplanes to the Red Sea port of Rabigh, further north along the coast from Jeddah. Lawrence persuaded Abdullah that in order to appreciate fully the possibilities of an Arab revolt, he needed to meet with each of Hussein's sons. Abdullah was so impressed by Lawrence that he made representations on Lawrence's behalf to his father and obtained permission for Lawrence to journey into the interior of the desert to a place called Wadi Safra in order to meet with another of the sons, Feisal ibn Hussein. Upon his first meeting with Feisal, Lawrence wrote, "I felt at first glance that this was the man I had come to Arabia to seek - the leader who would bring the Arab Revolt to full glory." (34)

Lawrence returned to Cairo from Arabia in November 1916. He was soon back on the Peninsula, however, joining with Feisal in Yanbu in December 1916 to begin a campaign of guerrilla warfare. Using the desert as a shield, the Arabs, with Lawrence, attacked the Hejaz Railway that ran south to Medina. Although only a minor irritant, the attacks nevertheless prevented Turkish reinforcements from reaching Medina. The bedouin who rode with Lawrence dubbed him, "Emir Dynamite." (35) Lawrence became Arab, in appearance and life style, which given the harshness of the terrain and climate made for great self-deprivation on his part. (36)

On 6 July 1917, Arab forces captured Aqaba, a garrisoned port held by the Turks and located in south Palestine on the Red Sea. The port was equipped with shore batteries that faced the water and which prevented the Royal Navy from entering the northeastern finger of the Red Sea, a route necessary for securing Palestine. (37) The victory at Aqaba cleared the way for an imminent British invasion of Palestine, and the capture of this strategic port convinced Lawrence of the effectiveness of the Arab force and fueled his resolve to fight for the Arab claim for an independent state.

Against the background of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 and the Balfour Declaration in 1917, Lawrence continued to promise the Arabs that Britain would honor the right of the Arabs to set up an independent state after the war. Lawrence had no authority to do so, yet in order to have the Arabs continue their campaign against the Turks, he felt that he had no other choice. (38) It is still not clear when Lawrence became aware of the secret British agreements relating to the Near East, but he was aware, though, that the British were not convinced, as the war progressed, of the validity of the Sykes-Picot agreement. (39)

Thanks to Lawrence and the Arabs, the British not only successfully invaded Palestine in the autumn of 1917 but continued north into Jerusalem, reaching the city on 11 December. From there they advanced into Damascus in September 1918, right into the very heart of Syria.

On 1st October 1918, Lawrence and the Arabs entered Damascus, two days after Australian troops. Victory against the Ottoman Turks had been achieved. Later, Lawrence was to insist that the Arabs had conquered Damascus, (40) and as a result, they were entitled to lay claim to Syria. Unfortunately, while in the midst of celebrating the capture of Damascus, the Arabs' seemingly incurable factionalism (Lawrence had witnessed it during the desert campaign) once again erupted. (41) The factionalism was to show itself again during the Peace Conference when Hussein would find himself at odds with his neighbor to the West of the Hejaz. (42)

Ibn Saud (43) was another player in the Arabian Peninsula that enjoyed the support of the British. He was gradually assuming control of the central and eastern provinces of the peninsula with encouragement and support from the Anglo-India Office of His Majesty's Foreign Office. The Anglo-India Office was mindful of the need to preserve and safeguard routes to India, and had been looking to the possibility of air routes being opened up between Britain and India. (44) It also was crucial to British interests that the whole of the peninsula, not just the Hejaz on the western boundary of the peninsula, should be friendly to the British.

Ibn Saud was the chosen man of the British to safeguard British interests in the central and eastern parts of the peninsula. He practiced a variation of Islam known as Wahhabi. (45) This variant of Islam spread westwards as ibn Saud took more and more control of the central provinces until he reached the Sunni controlled Hejaz region. Soon, there were skirmishes occurring between Hussein's Sunni Arabs and ibn Saud's Wahhabis. (46)