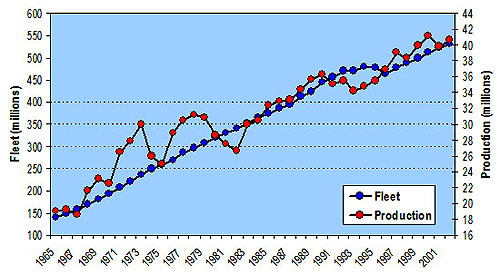

- Number of cars in the world

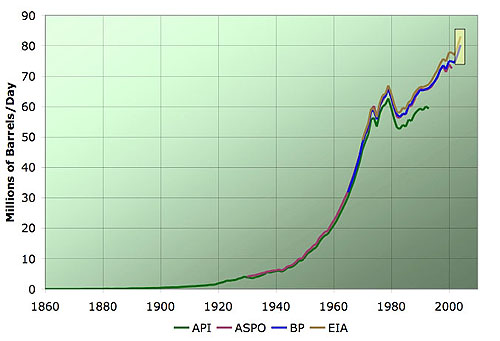

- Crude oil production

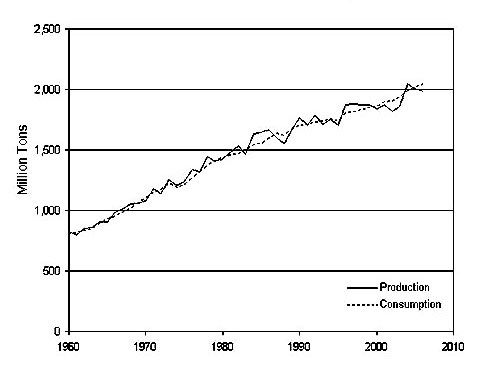

- World grain production and consumption

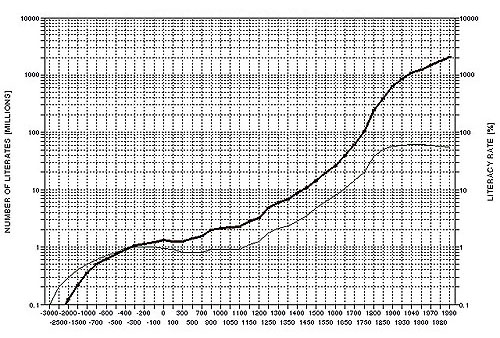

- Literacy rate

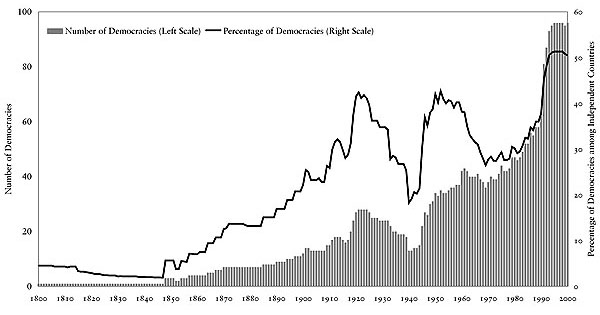

- Number of democracies in the world (note how that graph levels off and then begins to descend)

Number of Cars in the World

Source is www.theglitteringeye.com/images/carprofleet.gif citing the Worldwatch Institute

Crude Oil Production

Source is www.theoildrum.com/uploads/12/world_context.jpg

World Grain Production and Consumption

Source is www.jennifermarohasy.com/blog/archives/2006_ProductionConsumption.gif

Source:

Source:Literacy Rate and Literate Population

Source is brucegary.net/book/fig15p12.gif

Number of Democracies in the World

Source is media.hoover.org/images/policyreview135_boix1.gif

It certainly looks like the world is more "democratic" today than it was sixty years ago, and there are some other reference sources that claim is so. Look at what the popular Wikipedia notes in its entry on "democracy":

The number of liberal democracies currently stands at an all-time high and has been growing without interruption for some time[citation needed]. Currently, there are 121 countries that are democratic, and the trend is increasing[10] (up from 40 in 1972)[citation needed]. As such, it has been speculated that this trend may continue in the future to the point where liberal democratic nation-states become the universal standard form of human society. This prediction forms the core of Francis Fukayama's "End of History" controversial theory. These theories are criticized by those who fear an evolution of liberal democracies to Post-democracy, and other who points out the high number of illiberal democracies.

Encyclopedia Britannica Online (Retrieved 22 January 2008 search.eb.com/eb/article-233845):

During the 20th century, the number of countries possessing the basic political institutions of representative democracy increased significantly. At the beginning of the 21st century, independent observers agreed that more than one-third of the world's nominally independent countries possessed democratic institutions comparable to those of the English-speaking countries and the older democracies of Continental Europe. In an additional one-sixth of the world's countries, these institutions, though somewhat defective, nevertheless provided historically high levels of democratic government. Altogether, these democratic and near-democratic countries contained nearly half the world's population. What accounted for this rapid expansion of democratic institutions?

American interest in making the world more democratic was largely non-existent before World War I. Then, on 2 April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to ask for a Declaration of War against Germany in order that "The world must be made safe for democracy."

World War II would bring a similar American mission, though President Franklin D. Roosevelt couched it in somewhat different terms in his Annual Message to Congress (6 January 1941):

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression--everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way--everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want--which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants-everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear--which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor--anywhere in the world.

Then after the successful conclusion of the Second World War, the real essence of the Cold War was always to combat the spread of communism (and, I would argue, secondarily to increase the spread of democracy). Harry Truman, in his Address to Congress of 12 March 1947, in stating what would become known as the Truman Doctrine, averred that:

I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.

I believe that we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way.

President Jimmy Carter, decades later, in his inaugural address, also spoke in terms of the American commitment to the support of human rights--not necessarily "democratic" regimes or US allies--throughout the world. (See my comments on him in the 1970s.)

We could go through more presidential statements, addresses, sound bites, news conferences, etc. We could also examine the nature of the US commitment to worldwide democracy. Whether that commitment has been in terms of moral support, military weaponry, food assistance, volunteer workers, press statements, international diplomacy, etc? Whether it has been largely driven with the context of the Cold War and the idea of a "zero-sum" game?

But for much of the twentieth century, the US has shown some degree of commitment to furthering the democratic process abroad.

But what is the democratic process, and what is meant by democratization? There is actually little of real substance on the web, but I have suggestions for three good websites in this regard:

- Wikipedia is not a bad place to start with its definition of democratization,

including a list of thirteen factors affecting the democratic process

(take a moment to click on the "discussion" tab at the top of the

article to get some sense of the ongoing discussion of this entry)

- The Comparative Democratization Project

at Stanford University (It is a bit awkward to navigate, and some of

the materials are getting out-of-date, but there is still some great

research there)

- Democratization by R. J Rummel, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Hawaii, is a readable introduction to the subject with some very good reference links.

And what exactly is meant by democracy?

That can be a difficult question to answer because no one really can agree on a definition of what democracy is. The ancient Athenians had a different answer than the citizens of the Roman Empire, and those answers are different than what a present-day American might put forward--not to mention the fact that different political parties in the United States will all have their own perspectives on democracy--and the American definitions are different than someone from Indonesia or Kenya or Russia.

From the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary: "government by the people" or "rule of the majority" or "a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections." You can also look at the above citation from Wikipedia or Encyclopedia Britannica or check the US Department of State's What is Democracy?

So why are there more--but not all that many more realistically--democratic countries in the world today? Is it better communication and technology? What about some of the factors that were on the charts above? Do you think that there is any correlation between any of those factors and the increase in the number of democratic regimes in the world?

Here is my attempt at

an answer to the question of why there are more democratic countries in

the world today? I would point to these factors. which are in the order

that I thought of them:

- Communication. The world truly is a smaller place today with the extent of the communication revolution that has gone on since really the 1970s--just look at the difference between the single, rotary-dial telephone to the picture-taking, web-accessing, cell phone of today. The improvements in communications have given more people access to more information (and rather more cheaply too), all people the ability to communicate easier and more reliably with one another and interested people the opportunity to organize/mobilize with like-minded individuals.

- The United Nations and other international organizations, such as Amnesty International, the African Union, Organization of American States, Human Rights Watch, etc. The continuing advocacy of these organizations has made a difference. In most cases, the pressure is really mostly peer pressure, sometimes it is effective, sometimes it is not. But the deployment of peacekeeping forces does help.

- Education. Simply put, there is more education in the world today, and there is more access to that education. True, there are still inequalities in this regard, but a lot more people can read and write today, and a lot more people have gone on to higher education. The more educated people are, the more active they generally want to be as part of the government. (did I really write that?)

- Transportation. The more cars in a society, the more likely it will be democratic. Is that far-fetched or not? But this point also involves the ability of people to migrate back and forth across borders, to the United States and back, to visit other democratic countries and see first hand.

- The Middle Class and its growth. Wherever a rather larger and vibrant middle class has emerged as a buffer between the very rich and the very poor, the prospects for a transition to democracy improve.

- Money. Most of the poorer countries in the world are not democracies, but then again many of the world's richest countries are not democracies either!

- Money. Back to the idea of international advocacy, which can exist in a monetary form. For example, I do think that international economic sanctions played some role in the reversal of apartheid in South Africa. How much, though, I am not quite sure. But the money does not guarantee a democratic government. For example, note all the money that the United States pours into Pakistan.

- Power of the media: radio, television, satellite communications, the web.

- The symbolism and imagery of democracy--but not necessarily a real democracy--This used to be quite common in the communist regimes of Eastern Europe.

- What is very clear to me is that the process of democratization is not a process that can be consciously manipulated from the outside of a country. While many of these factors can be tinkered with to improve the chances and make the conditions better, in the end, the transition to democracy must be worked out on an internal stage by internal figures and people.

- Failure of other alternatives. The communist alternative has not worked out well in either its Russian or non-European forms--there have been many varieties. There have also not been a plethora of benevolent dictatorships or authoritarian regimes that really improved the lives of people in their societies either. So, what is left?

- Image of the United States. Though a bit tarnished in recent years, the United States was always a vision to others throughout the world. The Statue of Liberty was there, a shining beacon of democracy. America stepped up in Two World Wars for "freedom." That made people believe that there might be something good after all to the idea of democracy; democracy inspired many around the world.

Maybe there are more democracies in the world; but we could also take a quick look at the "quality" of those democracies. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy (*.pdf file) by Laza Kekic does just that. Although there is considerable academic disagreement over just how to "measure" a democracy, the Economic Intelligence Unit adopts five categories. In Table 1 of that report, 165 independent states and 2 territories in the world are ranked from full democracy, to flawed democracy, hybrid regime and then authoritarian regimes. Just in case you do not want to look yourself: Sweden is first; Canada is ninth; the United States is seventeenth; and North Korea occupies position 167.

When summarized (Table 2), we can see that 13% of the world's population lives in full democracies (28 countries); 38.3% in flawed democracies (54 countries); 10.5% in hybrid regimes (30 countries) and 38.2% under authoritarian regimes (55 countries). That means that despite the advances of democracy in the last half century, almost 50% of the world's population lives in regimes that are probably not democratic (over half the countries in the world), with a huge percentage of the world living in clearly authoritarian countries.

Web pages within the course relevant to the issue of Democratization

Some suggestions for further research

- Russell Dalton, Doh Shin, Willy Jou, Understanding Demo car a cy: Data from Unlikely Places (*.pdf)

- Kenneth Wollack, Assisting Democracy Abroad, Harvard International Review (23 December 2010)