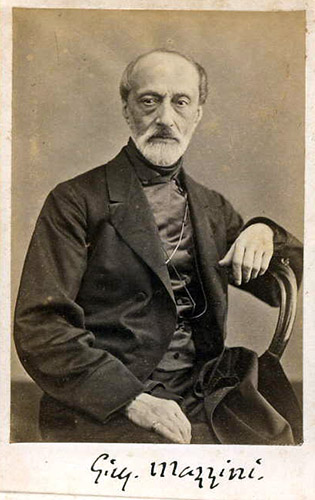

Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) was one of the four most important figures of the Italian Risorgimento ("the-putting-together-of-a-unified-Italy").

The other key individuals were the radical revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-82); Camilo Benso, count di Cavour (1810-61, prime minister of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia); Victor Emmanuel II (1820-78, king of Sardinia and then king of Italy). The Risorgimento was a lengthy process that began in 1815 with the Congress of Vienna and ended in 1871 when Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy.

It is interesting, but not necessarily important, that while one man was largely responsible for the unification of Germany (Otto von Bismarck, 1815-98), it took four men to unify Italy.

After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the Congress of Vienna re-established on the Italian peninsula the earlier conglomeration of independent kingdoms that had existed before the Napoleonic wars: the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south, Piedmont in the north, the Papal States in the center, as well as other states like Venezia, Lombardy, Tuscany. Austria and the Hapsburg family as well as the popes were powerful forces opposing any unification of the peninsula.

Mazzini, who grew up in northern Italy, became a lawyer at the young age of twenty-four and soon was actively involved in a secret radical society known as the Carbonari. He was arrested, and after his release from prison he went into exile in Geneva, Switzerland. In the early 1830s he organized a new political society called Giovine Italia (Young Italy) to promote Italian unification through a mass popular uprising. Mazzini believed that only a popular revolution could create a free and unified Italy. “Neither pope nor king,” he declared. “Only God and the people will open the way of the future to us.”

In the 1830s Young Italy’s attempted insurrections were failures and ruthlessly repressed. In time these failures destroyed Young Italy as an organization. Mazzini himself was sentenced to death in absentia, and he wandered from place to place in these years, first in Switzerland, then in Paris and London. and eventually back to Paris.

During the revolutions that broke out across Europe in 1848, Mazzini returned to the peninsula, first to Milan where he tried to stir up a rebellion but that was crushed by the Austrian army. Then in February 1849 when a republic was proclaimed in Rome, Mazzini went there to become one of the leaders of the government, but that short-lived Roman republic was crushed by French troops aiding the pope. Mazzini had to flee to Switzerland.

Through the 1850s and 1860s, Mazzini continued to be active in supporting popular uprisings across Italy, but they all failed. Increasingly the key figures in the Risorgimento became Count Cavour and Victor Emmanuel II, and it was Victor Emmanuel II who became the new king of Italy (small version) in 1861.

The continued unification of Italy became tied to the events in Germany's unification. In 1866-67, as recompense for supporting Prussia in its war with Austria, Italy gained Venezia. Then as a result of supporting Prussia in its war with France in 1870-71, Italy gained Rome and the Papal States, now becoming the kingdom of Italy (large version) with Rome as the capital.

Mazzini had really played no role in any of the final steps of Italian unification. He died in Pisa in 1872.

Mazzini was an Italian nationalist, a democrat and a republican. As a nationalist, he devoted his life to creating a unified Italy free of foreign control. As a democrat he believed in universal education and that democracy must be a key component of a future free and independent Italian republic. As a republican, he refused to declare his allegiance to any monarchy and also refused to participate in the Italian government under King Victor Emmanuel II. Mazzini had also believed that a popular uprising, not a diplomatic arrangement, should be the means to the creation of a united Italy and a democratic republic.

![]()

References

- Mazzini entry in Wikipedia (italiano) and Britannica

- Works by Giuseppe Mazzini at Project Gutenberg and at archive.org

- Short excerpt "On Nationality" by Mazzini

- Giussepe Mazzini

- SparkNotes on Italian Unification and the Wikipedia entry

- Il Risorgimento italiano (interesting YouTube video)

- Italian Unification | 3 Minute History

- For extra credit please suggest to your instructor a relevant website for this unit of the course. Send the title of the site, the URL and a brief explanation why you find the information interesting and applicable to the material being studied in this unit.